Il numero 1 del 2014 sulla cultura storica della Grecia

Il numero 1 del 2014 sulla cultura storica della Grecia

HISTORY IN PUBLIC OR PUBLIC HISTORY?

GREEK HISTORICAL CULTURE TODAY

by Giorgos Antoniou (International Hellenic University)

In April 2014 the city of Thessaloniki mayoral candidate for SYRIZA (radical left party), Tryantafyllos Mitafidis, entered the municipality and removed the pictures of two past mayors of the city. They were mayors that served under the Nazi occupation. The reaction to this gesture was mixed. Some historians warned that such a gesture was ill-conceived as the two mayors did not necessarily have typical collaborators’ profiles; the available evidence is not sufficient to prove their allegiance with the Nazis. Other commentators applauded the gesture, whilst a Holocaust survivor publicly thanked Μitafidis for finally taking the initiative to dishonor those who assisted/participated in the deportation of the Jewish population of the city.

Such public challenges to the dominant historical narratives are not rare in the Greek public sphere. They are partly a response to the excess of many kinds of official memories and commemoration of the past in Greek society. Desecration of civil war monuments, military graveyards or Jewish sites is more or less common. A new iconoclastic trend has recently appeared in the shape of intense protests during school and military parades celebrating the two most significant moments of the Greek nation: the war of independence (celebrated on 25th march) and Greece’s entry into the second world war (28th October). These parades were extremely popular in the past. Thousands of people attended in celebration of the moments the nation fought as one against its enemies. Recent disruptive protests began during the economic crisis and involved harassing the authorities and politicians attending the ceremonies or even flash mob parading of the unemployed or trade unionists in front of the authorities. Such tensions undermined the unilateral meaning of the ceremonies and their symbolism of a united nation; the government decided to control crowd participation and members of the police who could attend. As one of the authors in this volume claims, the recent economic crisis has motivated people to move beyond the heroic hegemonic narrative of the last decades and to invent other narratives in order to explain their current situation.

This form of ‘negative’ or inversed reading of the past in public, however, is one of the past’s few uses in the present encountered in Greek society. During the last ten years public history has increased in significance as a historical field. This is especially true in the United States, where it first flourished and continues to rapidly grow and to a lesser extent in Europe. Public history, widely construed, is history outside academia. As history reduced to its minimal meaning can be two things, a) past events and b) the genre of writing about these events, public history can be two different things: a) the commercial, cultural, instrumental, symbolical, experiential diffusion and presence of the past around us and b) the study of this phenomenon within and outside academia, certainly with a self-reflective method and approach.

In this respect, countries such as Greece find themselves in a peculiar position. While history has played and continues to play an immense role in Greek political life and society in general – few would disagree that Greece is a past oriented society – there is little elaboration or processing of this past in terms of its public uses. In other words, there is a discrepancy between the public uses of the past in the Greek context and the need to elaborate on the perceptions of this past in contemporary Greek society. To put it simply, Greece is an extremely rich soil for the study of the presence of the past in today’s life. But, outside academia, there is no culture of reflection and self-reflection on this role of the past. Even within academia, there is a relative lack of interest in the fields that comprise important aspects of public history study.

As a working hypothesis, one might argue that the less important the past is for a specific society the most elaborate and academic the relation of this society is with her past. Vice versa, the most vital and repressive the mix of past and present is in a society, the less this society is aware of the tropes in which this relationship emerges and continues to influence people’s everyday reality. With few notable exceptions, public uses of history in historically overloaded countries with troubled histories become a burden and not an opportunity to tackle such issues as the formation of national identity, the deconstruction of historical myths, the recognition of otherness or the subaltern subjects of history in general.

One explanation about this contradiction may lie in the role that agents of history play in these societies. Where reconciliation has not emerged, or the state fails to address past wounds and traumas, the role of agents of historical memory becomes vital. Despite this trend being partly based in what one would today name as civic society, this role can frequently be negative in the public dealing with the past since some groups of memory and history activists impose a narrow framework of interpretation of the past and a personalized agenda that favors individualistic interpretations. In other words, such pressure groups and agents of history privatize the public historical space and ostracize versions of the past that cannot fit into their individual narrative. As a result, the lack of trained practitioners and professionals of public history is replaced by a surplus of amateur ‘historians’ writing their own ego history in their own terms. This means that highly motivated -and quite often highly biased – amateur narratives of the past dominate whole areas of research and historical fields. That trend has also been exacerbated through the new social media and the democratization of narratives about the past. Are these observations bad news for the public role of history in present society?

It is true that many times the issue of public history and the past is linked to a number of social, cultural and political elements that interrelate with and influence each other. For instance, beyond historical accounts, monuments and public celebrations, representations of the past in genres like cinema, the internet, oral tradition, theatrical plays, textbooks, art, comics, memoirs, literature and photography show the fragmentation and ‘democratization’ of the flow of memories in current societies; a fragmentation that is reflected in the emergence of new categorizations of memory makers, mediators, agents and consumers. In other words, historians have lost a large part of their primacy over the past, especially in the public sphere. Their right to be considered as the centre of historical representation, the ‘normality’ from which all attempts to deal with the past should emerge and to which they should return is seriously challenged by these new trends in these new fields of public history. However, not surprisingly, these kinds of public memories and public pasts are very hard to articulate, therefore a new kind of historian, outside university campuses needs to develop.

The present volume emerges from a conference that took place in Volos in August 2013 organized by the International Federation of Public History and the Civil Wars Study Group, an active group of Greek scholars who study conflicts both at Greek as well as at European level. The conference title was ‘uses and abuses of history; public history in Greece’. One thing became apparent from the start: the organizational committee, the participants and the audience all had a very different perception of what constitutes public history. From the very beginning the committee had to overcome a heated internal debate on whether history could be ‘abused’ in the public sphere (Dirk Moses, giving the key note lecture claimed openly it could not) or who the ‘abusers’ might be. The conference was almost cancelled on account of these serious disagreements on what history and public history may encompass today. Other points in a passionate exchange of emails and discussion before and during the conference included the critical approaches to memory studies as a genre, the fight against postmodern interpretations of the past, the responsibility of historians to contribute to the public sphere and what that may mean for the profession. The audience on the other hand was anything but passive. By picking upon the title of the conference, teachers of history in secondary level education protested openly about the distance between academia and the public and pointed out that professional historians should be able to simplify and disseminate more successfully the products of their research: otherwise, as one of them asked, what was the point of writing history?

The eight articles this volume contains differ significantly but elucidate the current trends and concerns of Greek academia on the diffusion of historical knowledge in the public sphere. The present volume’s contributions are representative of major public history issues that stir up much debate and controversy. The articles analyses a) moments of major national identity issues that re-emerged and needed to be resolved, b) dealing with the past’s taboo issues and, c) current trends in public history.

The articles of Andreou-Kasvikis and Katsanos deal with what is called “the Macedonian question” in Greece, since the end of 19th century aspiration to annex the Macedonian territory. According to the great idea of the 1800s, the Greek nation and the leading nationalist spirit of the era, Macedonia was the ancestral land of Alexander the Great and therefore (since ancient Macedonians were nothing but a Greek people) belonged to the territory of the Greek State. This dream came true following the Balkan wars, when more than fifty percent of the geographical territory of the Macedonian land was annexed by the triumphant Greek state. Since then, the Macedonian question became a territorial integrity issue for Greeks; Greece was practically a status quo country that wanted to preserve the gains of the Balkan Wars, and believed that the term “Macedonia” was equal to the Greek Macedonian territory. Such views deliberately ignored the resentment and territorial revisionism by her neighbors throughout the 20th century. It was only in the 1990s that a surprised public opinion in Greece discovered that in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM), a strong Macedonian identity and (to a lesser extent) language were raising a new Macedonian issue that had to do both with current ethnic and national identities, the ownership of the Macedonian logo as well as with the claim to the heritage of ancient Macedon in the present. Andreou and Kasvikis examine the commemorative practices of the two rival mnemonic legacies of Thessaloniki and Bitola through a comparison of two statues of the same ancient Macedonian king. Therefore public sculpture becomes one of the battlefields of the war on symbols over the past. History on the other hand, as Katsanos’ article shows, played a similar role. The official state narrative, Katsanos claims, about the history and the past of Macedonia was not so much an outcome of state intervention; it was rather the outcome of the historical and political agenda local and state agents imposed on the state. These agents demanded and succeeded to transmit their version of history in public and continued a war of history throughout the entire postwar period. When this history war (of words) transformed to a diplomatic one, each state had its (historical) nuclear arms and no hesitation to use them, only to further poison diplomatic relations and possible solutions.

The dealing with the past of taboo issues is another complex process that takes place right now, fourteen years into the 21st century, in Greece. While the economic crisis overshadowed many aspects of the historical past, it has renewed certain of its aspects that were either ignored or misinterpreted. This has not always been a fruitful experience. Public uses of a precarious past led many times to conspiracy theories or simplistic, populist approaches to complex phenomena. For instance, the matter of Nazi war retributions was one of the most discussed issues in the public sphere in recent years for many reasons, one of which was an attempt to regain self-esteem and national pride vis-a-vis the unpopular Germans who are perceived to have imposed on Greece a new type of –economic- occupation. Many of the mainstream political parties made direct comparisons between the two Occupations and Chancellor Merkel with Hitler; while the most common derogatory term to describe the supporters of the current government is that of ‘collaborators’. In such cases one can easily trace the ingredients of current historical misconceptions both about the past and the present in relation to anti-German sentiments of a large part of the Greek population.

Civil War memories have remained unspoken for many decades, in spite of being deeply impressed in individual and family memories. This anti-representational nature of Civil Wars explains the discrepancies and similarities between some forms of testimonies to other forms (for instance the tensions between oral interviews and written memoirs) and the discrepancies between historical narrative and the subject’s experience. In such cases silence perhaps plays the most crucial role in the memory and the representation of the events. The Greek Civil War that followed Axis Occupation is typical in that respect since the anticommunist regime of the years 1949-1974 muted alternate versions of the past.

It is not surprising that the advent of democracy in Greece in 1974 revealed, hitherto silenced versions of an officially uncontested but essentially precarious past. It took more than twenty-five years for Greek society to admit the intra-national, civil character of the conflict of the years 1946-1949. Still, a considerable part of Greek society reacted to this novel point of view with extreme passion and consistency. A first significant change was the long delayed incorporation of the legacy of the resistance into the Greek political system. The article of Paschaloudi and Antoniou shows how complex and slow this process was in the period where anticommunism was prevalent. But also, how difficult it remained to compensate the resistance veterans both symbolically and economically in a fair way. In many respects, the Resistance legacy was doomed to be linked with that of the Civil War, a taboo that was not broken even with the establishment of a democratic regime in Greece in 1974. The memory preservation, formulation, negotiation, oppression, and suppression of the civil war, contributed to the political manipulation of this ambiguous past in contemporary politics. Memory and history became a favorite battleground for politics and supplied the different strategies, concepts, narratives each side adopted in securing optimal exploitation of the civil war heritage.

Dordanas’ article compares the german Historikerstreit with the revisionist ‘new wave’ in Greek 1940s historiography, Dordanas shows the difficulty professional historians faced when they were read by the wider Public. As it seems, quite often the winner in a historiographical battle can be the looser in the public sphere. This brings back the question of how to disseminate the outcome of historical research into the public sphere; to put it simply, how one can prevail over fiction or Hollywood with Jstor (the famous database of scholarly works). However, as Dordanas shows, such debates refer to wider social and national identity questions, they do not, therefore, only belong to historians. What also becomes clear is that at the end of the debate nothing remains the same; the field changes, public awareness of the past increases, polarization appears, history once more gains relevance for everybody.

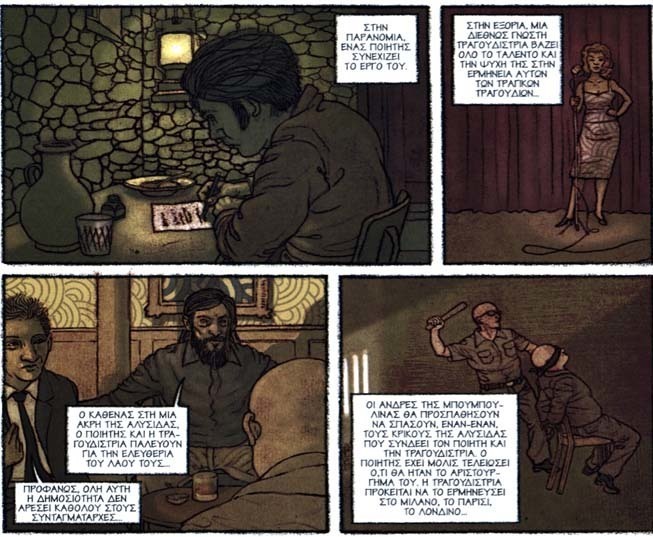

A. Gefe and J.L.Bocquet, Το τραγούδι της Λένας [Lena’s Song], Athens, Mamouthcomix, 2009

The article of Kornetis deals with another great taboo of the recent past. The issue of torture during the seven-year-long dictatorship (1967-1974) and the public discussion about it reveal a wide range of reactions that signify the limits or representation in public for a society that had to reinvent itself. Successive or parallel – but significantly different – memorial strategies of institutional organizations such as the state (or political parties) and the individual involved a) memory repression, b) silence as a medium for superficial and temporary consensus, c) amnesia as a proposal for permanent reconciliation in society, and d) contestation which inevitably arose as a result of the long term political, cultural, social distortion the civil war and the dictatorship produced in Greek society.

The last set of articles deals with aspects of contemporary public historical culture in Greece. The article by Athanasiades studies the most significant public debate of the last two decades, about the notorious 6th grade primary school history textbook. The textbook was criticized from many different directions, while historians were divided. Some considered its modernizing, anti-nationalist point of view a much needed contribution. Others focused on its obvious historical errors and simplifications. It was the mobilization of the extra-academic community that was decisive in the bitter end of that debacle (the textbook was withdrawn). Large groups of internet activists denounced the book and attacked personally the author; as a result of this wave of negative publicity, public opinion very soon turned against it. In that sense, this case study is indicative of the power that civic society, or pressure groups, have in setting the agenda over the past and its uses.

Mitsos Bilalis theorizes on this power by analyzing the ways the internet influences current historical culture. The author shows how the new social media not only disseminate various opinions and facts about the past but also create new types of mnemonic subjects and new types of historical cyberspaces. These cyberspaces exist in parallel with traditional historiographical space and quite often are an inverse image of it. The rather dire conclusion is that the role of multiplier is much more significant than the role of the historian in cyberhistory. The theoretical question Bilalis might ask is how could historians find a role in this new parallel universe.

The last article by Vervenioti shows that in this new historical ecosystem of the public sphere, grassroots initiatives and activism do not only lead to polarization or the hijacking of history by internet activists. Vervenioti describes and analyzes the reasons behind the flourishing of oral history groups in Athens and elsewhere. A mixture of dedicated professionals of oral history and amateur researchers proved that the model of individual research, in social sciences, has serious disadvantages compared to collective projects open to wider audiences. This new type of ‘open source’ research reminds the major advantage of history: to provide a meaningful past for subjects and to fill in the gap between academia and the public, with terms and conditions positive and not hostile to academic standards and research. This in-between space is where the future of history and historiography in public will be decided and projects of this nature will become crucial for establishing new bonds between history and the general public. As it becomes apparent with this volume, this is not optional anymore.

Indice